In the absence of a solution by government entities, Camas citizens act to address pollution at Lacamas Lake

Seven years ago in January 2014, Lacamas Shores homeowner Steve Bang began digging into the issue of the biofilter owned by the Lacamas Shores Homeowners Association (LSHOA). A group of roughly 50 homeowners came together joining the effort. It was the beginning of a lengthy journey into water quality issues, biofilters, and a ton of government rules, regulations, and bureaucracy.

What had once been a nice meadow of grasslands in the mid 1990’s, had become an overgrown mess; tons of weeds, scrub trees and underbrush. As Bang and his neighbors were to eventually learn, the “filter” was supposed to clean the stormwater from the Lacamas Shores subdivision. Instead it was adding pollutants to Lacamas Lake.

Local citizens have experienced one aspect of the failed biofilter. “It is the only known contributor of phosphorus proven to be exceeding its compliance standards,” said Marie Callerame. “Phosphorus feeds the growth of toxic algae in the lake.” In the summer of 2020, her boys refused to swim or play in the lake water. It became toxic — “they could feel the film of the bad water,” she said.

Callerame had joined Bang in researching the issues in 2014, collecting and collating a huge amount of research and data on lake water, biofilters and government water quality regulations.

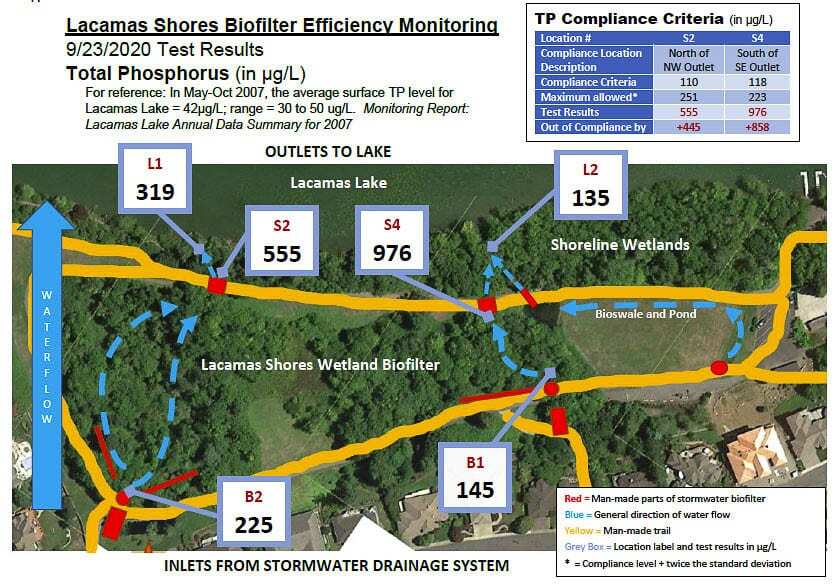

In the fall of 2020, Callerame enlisted the help of other concerned citizens to test the water entering and exiting the LSHOA biofilter. They paid a private firm to test water samples they collected, and Clark County Today was there to document the collection process. The phosphorus, conductivity, and total suspended solids were measured and reported by Columbia Laboratories in Portland.

Stormwater enters the biofilter area via stormwater drain system “bubblers” at two locations on the uphill, south side of the Lacamas Shores biofilter. (See graphic B1 & B2). It is supposed to be spread out from the bubblers, but contained within the nearly six-acre biofilter. Natural grasses and plants begin the process of cleaning the water as it ultimately soaks into the ground and into the water table. Any water that continues on as surface water, is supposed to flow into the lake at a slow, gradual rate to allow for the plants and grasses to “clean” the water.

What Callerame found was the water flowing out of the biofilter and into the lake was polluted with more than five times the amount of acceptable phosphorus and a 10-fold increase in total suspended solids. The amount of phosphorus in the water increased as it flowed through the biofilter, adding to the problem. The biofilter did the opposite of what it was intended to do.

In fact all three items measured (phosphorus, conductivity, and total suspended solids) were not only higher leaving the biofilter, but exceeded state water quality standards by substantial amounts.

“It was stunning how much more phosphorus was being added to the stormwater as it flowed through the biofilter,” said Todd Schoenlein. “It’s not cleaning at all. Instead, it’s making the pollution worse.”

Schoenlein is president of a different Camas neighborhood HOA and is responsible for the care and maintenance of their biofilter. He joined Callerame and botanist Rodger Hauge in collecting water samples from the LSHOA biofilter, roughly 30 minutes after a rain shower began on Sep. 23.

The phosphorus entering the eastern stormwater facility measured 145 micrograms per liter. The outflow next to the hiking trail showed 976, and 135 micrograms at a second spot nearby after being diluted with a separate water source. The phosphorus amount increased well over six times at one exit point.

The western stormwater facility measured 225 micrograms per liter entering the biofilter, with the outflow at 555 micrograms at one location and 319 at another. The phosphorus in the water increased by 50 to 100 percent.

As reference, phosphorus in Lacamas Lake water measured in a range of 30 to 50 micrograms per liter in a 2007 water quality report by Clark County Public Works.

“The concept of a biofilter is to stop the water from flowing directly into a lake, into a stream, and have it soak through the ground and get into the aquifer,” said Hauge. “And in that process of soaking into the ground to the aquifer, it gets cleaned.”

A properly functioning biofilter acts like a scrubber, removing all the phosphates and nitrates and chemicals from the water as it soaks into the ground and the aquifer. Some of it is consumed by the plants as well.

Lacamas Lake is a highly eutrophic lake according to Hauge. A eutrophic condition is a term describing a situation where a water body has lost so much of its dissolved oxygen that normal aquatic life begins to die off. Eutrophic conditions form when a water body is “fed” too many nutrients, especially phosphorus and nitrogen.

History of the Lacamas Shores biofilter

In 1988, the original developer was awarded a “Shoreline Development” permit by the city, in compliance with the Shoreline Management Act of 1971. Subsequently an Agreed Order of Remand by the Shoreline Hearings Board stated the following:

“The developer agrees to commit a portion of the property now reserved for potential wetland use to be developed immediately as part of the man-made wetlands created as part of the biofilter storm drainage system (emphasis added) on the project. This additional property is depicted as “newly created wetlands”.

The permit included language requiring the developer to create and monitor a biofilter to handle stormwater. It also passed that obligation to monitor and maintain the biofilter on to the homeowners association, once development was 75 percent complete.

A 1988 Camas permit, a Department of Ecology (DOE) approval, and a subsequent order by the Shorelines Hearing Board all approved the development including the creation of a biofilter to handle stormwater.

The 1988 DOE letter stated: “The emergent wetlands (LS biofilter) adjacent to the forested wetland will be greatly enlarged by the storm drainage system. As such we are willing to allow for some manipulation of this system to enhance its filtering capacity should future monitoring show such a need.”

A 1993 revised permit stated in part: “The storm water disposal system serving Lacamas Shores consists of a bio-filter system and bubbler system.” It later states: “Soluble and total phosphorus entering the lake from the wetlands are at concentrations at or below the compliance levels . . .” An evaluation by Beak Consultants states: “The bubbler/biofilter/settling pond system provides several redundant features that will ensure the water quality of Lacamas Lake.”

In 2004, Clark County studied Lacamas Lake water focusing on “Nutrient Loading and In-lake Conditions.” They reported the lake had a “high level of algae production.” They further reported:

“Water quality problems associated with Lacamas Lake eutrophication in 1984 included severe dissolved oxygen depletion, poor water clarity, high levels of algae growth, nuisance blue-green algae blooms, and dense beds of aquatic macrophytes. These conditions are typical of a highly eutrophic lake, and were attributed primarily to excessive inputs of the nutrient phosphorus due to human activities in the Lacamas watershed.”

One graphic showed total phosphorus from 1984 through 2003. The text stated: “Overall, data from the more recent years indicates a significant decrease from the concentrations observed in 1984.”

The 2004 report included: “Nitrogen is the second major plant nutrient of interest in lakes. In the presence of sufficient phosphorus, elevated nitrogen levels may also cause excess algal and plant growth.” They reported an increase in nitrogen over the 1984 to 2003 period.

The 2004 report’s conclusion included: “Total phosphorus concentrations in the creek and lake are much lower today than when first measured in the 1970s and 1980s.” Furthermore, “In assessing the long-term information available for Lacamas Lake, it appears that early efforts in the watershed successfully decreased phosphorus inputs.”

A 2010 Clark County water quality report showed Lake Vancouver in “poor” health, whereas Lacamas Lake and Battle Ground Lake were in “fair” condition.

Somewhere between 1993 and 2020, the biofilter failed. It is adding phosphorus and other elements into the stormwater being dumped into the lake. From 2012 to 2017 no algae blooms were reported. It appears no water quality testing was done in 9 of 11 years from 2007 through 2017. Algae toxin levels didn’t exceed state guidelines until 2018.

In Dec. 2019 testing by Camas, phosphorus and total suspended solids readings were more than two standard deviations above compliance levels according to Callerame.

The standoff

In July 2017, the LSHOA gave a proposal to the city of Camas. They wanted to perform maintenance on the biofilter. “We would like to return parts of the system to a healthy well-vegetated widespread wetland buffer habitat with grasses, and other wetland plants for proper bio-filtration.” Expected costs for their proposal was about $30,000.

In Feb. 2018, the Camas city attorney wrote the LSHOA. He claimed the biofilter was a “wetland” rather than a biofilter. But later stated the LSHOA stormwater facility should do three things.

- Be capable of accepting the stormwater coming into it from its intake;

- Effectively treat the stormwater; and

- Provide for appropriate outfalls of treated stormwater.

He then demanded a “conditional use permit be obtained” by the HOA.

A month later, a staff member of the Washington State Department of Ecology sent a letter to the city. It stated: “I have found no evidence to show that the wetland was constructed . . . for the purpose of stormwater treatment or detention.” They said they were “unlikely to approve a conditional use permit”.

“This was unbelievable,” said Bang. HOA bylaws state there is a biofilter that must be maintained. “The deed to my property obligates each and every homeowner to maintain the biofilter and stormwater system. The Washington Shoreline Hearings Board mandated the biofilter be created as part of the original development permit. They must have not been looking,” he said.

The city apparently forbade the LSHOA from repairing their biofilter, based upon the DOE letter.

Today, it has been shown that the biofilter is not capable of treating all the stormwater coming into its intake. Just 30 minutes after rain started on the Sept. 2020 water collection effort, two catch basins of the facility were bubbling over. Too much water was entering the system after a half hour of light to moderate rain.

If untreated stormwater is passing through outflows and into Lacamas Lake, it adds phosphorus and other pollutants to the lake water.

“What will the city do?” asked Bang. “Will they defend a source of pollution? Or will they finally demand that Lacamas Shores Homeowners Association finally fix the biofilter and fight for clean water?”

Don Trost, president of the LSHOA was asked about the position of the homeowners association. “We are aware of the concerns with the lake and are studying the matter at this time,” he said. “It is a topic before the full Board of Directors.”

The city of Camas did not respond to an email request for comment. They had been given the results of the water quality testing well over a month ago.

Area citizens want to be able to enjoy the lake for recreation. As Callerame said, she wants her boys to be able to swim and play in the lake every summer, like they used to.

The history of the toxic algae blooms has been sporadic until recently. There wasn’t regular testing of Lacamas Lake water until recently. Therefore, no reports of bad water quality were made.

A sudden “explosion” of toxic algae blooms occurred following a fall 2019 action by the LSHOA. After cleaning out stormwater distribution pipes in the biofiler, an algae bloom occurred within a month according to Bang.

In 2020, to many residents, it seemed like there was almost no time there weren’t “caution” or “warning” signs displayed around the lake. Reported testing results indicated toxic algae blooms occurred over a dozen times. Various “toxins” exceeded state guidelines multiple times during the year. Microcyctin exceeded state guidelines 14 times and anatoxin exceeded guidelines once.