Submitted by: Sarah Coccaro, member of the Land and Water sector of the Greenwich Sustainability Committee

Climate change is rapidly reshaping Long Island Sound. Water temperatures in eastern Long Island Sound (LIS) have increased over the past four decades, four times faster than the global ocean. Ocean acidification, another symptom of climate change, is also happening much more rapidly in LIS than elsewhere in the U.S. Cold water marine organism populations are declining. Sea levels are rising, increasing the frequency of flooding and erosion along our shorelines, which also impacts water quality in the Sound as it brings contaminants and sediments from onshore into the Sound.

Throughout the “One Water. Shared” series, we’ve looked into understanding where our water comes from, where it goes, and how to best steward this essential resource. In this final article, we look closely at our shoreline and LIS and how the health of the entire watershed depends on how we live on land.

Our Shellfish

A survey made by local commercial shellfishers calculated that Greenwich waters are the home to about twenty-five million oysters, close to one billion clams (hard and soft shell), and ten million mussels (blue and ribbed). An abundance of healthy shellfish in Greenwich waters and their natural filtration capabilities are a major factor in maintaining and improving water quality.

Nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, are essential for the terrestrial landscape, but an overabundance of these nutrients negatively affect Sound waters. Too much nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers runoff or seep into ground and surface waters, causing algae to grow faster than ecosystems can handle. Significant increases in algae harm water quality, food resources and habitats, and decrease the oxygen that fish and other aquatic life need to survive. Large growth of algae or “algal blooms” can severely deplete oxygen levels in the water undermining or killing off leading to illnesses and damage in fish populations. Algal blooms are also a risk to human health and can result in closed beaches.

Shellfish provide important services in the Sound ecosystem. Roger Bowgen, Shellfish Commissioner, says, “Each of these mature shellfish continuously filter the water they inhabit, removing algae, nitrogen and other contaminants. Daily filtration rates vary per species, e.g. oysters 50 gallons, clams 24 gallons and mussels 15 gallons. Based on the number of shellfish this calculates to billions of gallons of water being filtered per day. One estimate is that because of the number of shellfish in Greenwich Cove, it’s contained water is completely filtered twice a day.” A recent study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) determined that 9% of Nitrogen is removed from the Greenwich watershed annually by hard clam and oyster aquaculture, about 31,000 pounds of nitrogen per year. More than half of the local nitrogen input into Greenwich’s waters are from “nonpoint sources”, such as runoff from lawn fertilizers, which we learned from our previous article, “The Lowdown on Runoff: Keep Water Clean”.

In addition to managing the shellfish bed, the Greenwich Shellfish Commission takes samples of waters off Greenwich from 36 locations at a minimum of 16 times a year. These samples are taken to the Bureau of Aquaculture in Milford, CT for analysis to ensure water quality is not compromised. If there is an issue the shellfish beds are closed until the source of contamination is identified and resolved. In the event of bad weather that produces more than one and a half inches of rain, beds are automatically closed until samples are taken.

Over the last three years studies made in conjunction with UConn scientists, have been identified the presence of microplastics and polyfluoroalkyl (PFAS) substances in our waters. This important research is in addition to various projects the Commission has been conducting with NOAA over the last 5 years focusing on the importance of healthy shellfish beds and water quality and the value they bring to a municipality such as Greenwich.

Salt Marshes

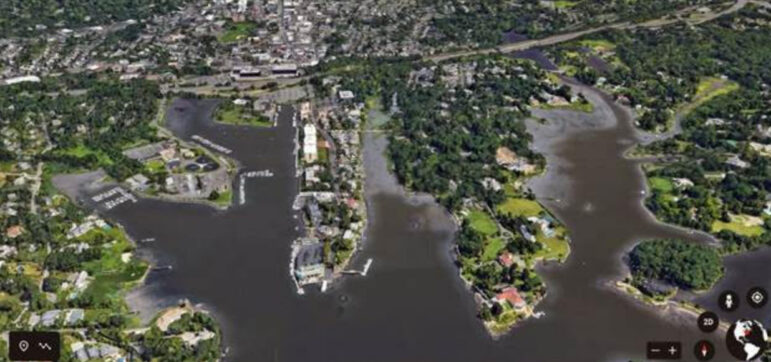

Salt marshes are coastal wetlands designed to flood and drain with tides and storms. They are our first (or last) defense in the nexus between land and water. The salt marsh ecosystems around LIS are critical habitats for a variety of flora and fauna, including ribbed mussels, fiddler crabs, shore birds, and saltmarsh cordgrass. They provide several ecosystem services, such as intercepting watershed-derived nitrogen before it reaches LIS, protecting shorelines from erosion by buffering wave action, and trapping sediments. They reduce flooding by slowing and absorbing rainwater and filter runoff, metabolizing excess nutrients. Knowing how they are affected by changes in the environment helps us protect them in the future.

Previous studies have established that high-nitrogen levels can decrease the health and resiliency of salt marshes through shifting biomass allocation, increasing decomposition, and causing bank instability, all of which can lead to increased marsh loss with sea-level rise.

Like shellfish, salt marshes are vulnerable to low oxygen levels that result in harmful algal blooms, changes in species composition and a decrease in water clarity. These impacts on species and ecosystem health are often amplified by multiple elements of climate change, including sea-level rise, rising air and sea temperatures, and increasing storm intensity and frequency. Conversely, low oxygen levels can exacerbate the effects of climate change by increasing coastal acidification, which carries its own set of negative consequences for marine and coastal species.

During Superstorm Sandy, sand dunes and their vegetative systems at Greenwich Point were pushed back into the town parking lot by a 10-foot storm surge. Hundreds of trees were knocked down, and many more died of saltwater exposure in the days that followed. Since then, community groups and the Town have been working to fortify the dunes heavily with native species to keep sand on the beach and out of the road. Replanting these areas helps to provide food and shelter for animals, and also stabilizes the soil.

Greenwich’s coastal area is one of the Town’s most important natural resources, providing a variety of environmental, economic, and community benefits. We need to understand the magnitude of the changes to the coast, from sea level rise and storm events, to mitigating our land use practices to bolster the resiliency of this treasured resource.

In this series we have talked about our water supply as a resource important to our economy and livelihoods. But water is much more than a resource. Water is responsible for all life on Earth. Understanding water in this elemental way ignites a reverence for it. The water that falls from the skies and is held in the land is the water we run our industries with, the water we drink, the water we bathe and play in, no matter where and how we live. It is One Water. Shared.

See also:

One Water: Capturing Rain and Keeping It on The Land

April 25, 2021

One Water: Water Doesn’t Fall from the Sky, It Comes from the Soil

April 16, 2021

The Lowdown on Runoff: Keep Water Clean

April 13, 2021

Water in Greenwich – Too Much? Too Little?

April 5, 2021

Our Changing Connecticut Climate: A Water Story

March 29, 2021

One Water. Shared: Greenwich Within the Long Island Sound Watershed

March 21, 2021