Mess with a sperm whale, get an 80-ton torpedo—one that will sink a ship and, like a giant mammalian Jaws, stalk the surviving crew across the ocean. That, at least, is the plot of Ron Howard’s cinematic rendering of In The Heart of the Sea. Based on the 2000 book by Nathaniel Philbrick, it’s a loose retelling of the 1821 sinking of the whaleship Essex, after an enormous sperm whale bashed in its hull with its head. The story eventually helped inspire Herman Melville’s 1851 novel, Moby-Dick, which describes a whaleship captain’s self-destructive obsession with hunting down the white sperm whale that sank a previous ship and severed his leg.

In the movie version of In the Heart of the Sea, the sperm whale goes beyond the historical account of the whale smashing into the Essex. It also hounds the whale boats in which the crew escape the sinking ship, ramming the small vessels and breaching on top of them.

This cetacean Cujo storyline squares with neither the chronicles of the Essex survivors nor with what we know about sperm whale behavior. The film “is doing a disservice to the whales,” says Shane Gero, a behavioral ecologist at Aarhaus University’s institute for bioscience.

“The aggression from [the film In the Heart of the Sea] and books like Moby-Dick are far from the reality at sea,” says Gero. “Aggression both between families and between males is very, very rare.”

In fact, nearly 200 years after the Essex went down, a huge mystery still hangs over the story: Was the sperm whale that attacked the Essex actually acting out of vengeance—and are these great animals even capable of such calculated violence?

Not just the Essex

It might seem that way given that the Essex was hardly the only whaleship to be rammed by a sperm whale. Others include the Pusie Hall in 1835, the Lydia and the Two Generals in 1836, the Pocahontas in 1850, the Ann Alexander in 1851, and the Kathleen in 1902 (all except the Pusie Hall and the Pocahontas sank). Another, the Union, went down near the Azores in 1807 after running into a whale in the night. These perilous encounters with sperm whales ended abruptly after the mid-1800s, thanks in part to the discovery of petroleum in Pennsylvania in 1859—a substitute for whale oil—as well as to rising wages, as Derek Thompson explained in The Atlantic. Another factor was that after 1850 most new ships were built not with wood but iron, which even an 80-ton whale can’t splinter. Tellingly, the last ship that sank due to a run-in with a sperm whale, the Kathleen, had been built in 1844, and was therefore made of wood.

The mystery of Mocha Dick

However, there might have been other sperm-whale attacks than just these seven—particularly if the legend of Mocha Dick is true. The story, first recorded by newspaper editor Jeremiah Reynolds, tells of a mammoth white whale near Isla Mocha, off the Chilean coast, that was famed for assailing whaleships. (As you probably have guessed, Melville took even more of his inspiration from the Mocha Dick legend than the story of the Essex.) The whale was said to have sunk some 22 whaleships between 1810 and 1830.

New clues from the sea-bottom near Isla Mocha hint that there may indeed be some truth to the legend, says Juergen Stumpfhaus, a documentary filmmaker whose film Der Aufstand der Wale explores man’s relationship with sperm whales. Footage captured by the Sonne, a research vessel mapping a deep-sea canyon near Isla Mocha, revealed a graveyard of whaleships thousands of meters down. The area also teems with giant squid, which making it a prime hunting ground for sperm whales. In the clip below, the section on the Sonne‘s discoveries starts at 29:00. (Note that the documentary is in German; Stumpfhaus says the Smithsonian Channel will release an English-language version in the next year.)

Yet even if Mocha Dick did bring that whaleship attack tally to 29, take into account the scale of the whaling industry’s slaughter and it seems surprising that whales struck ships as seldom as they did.

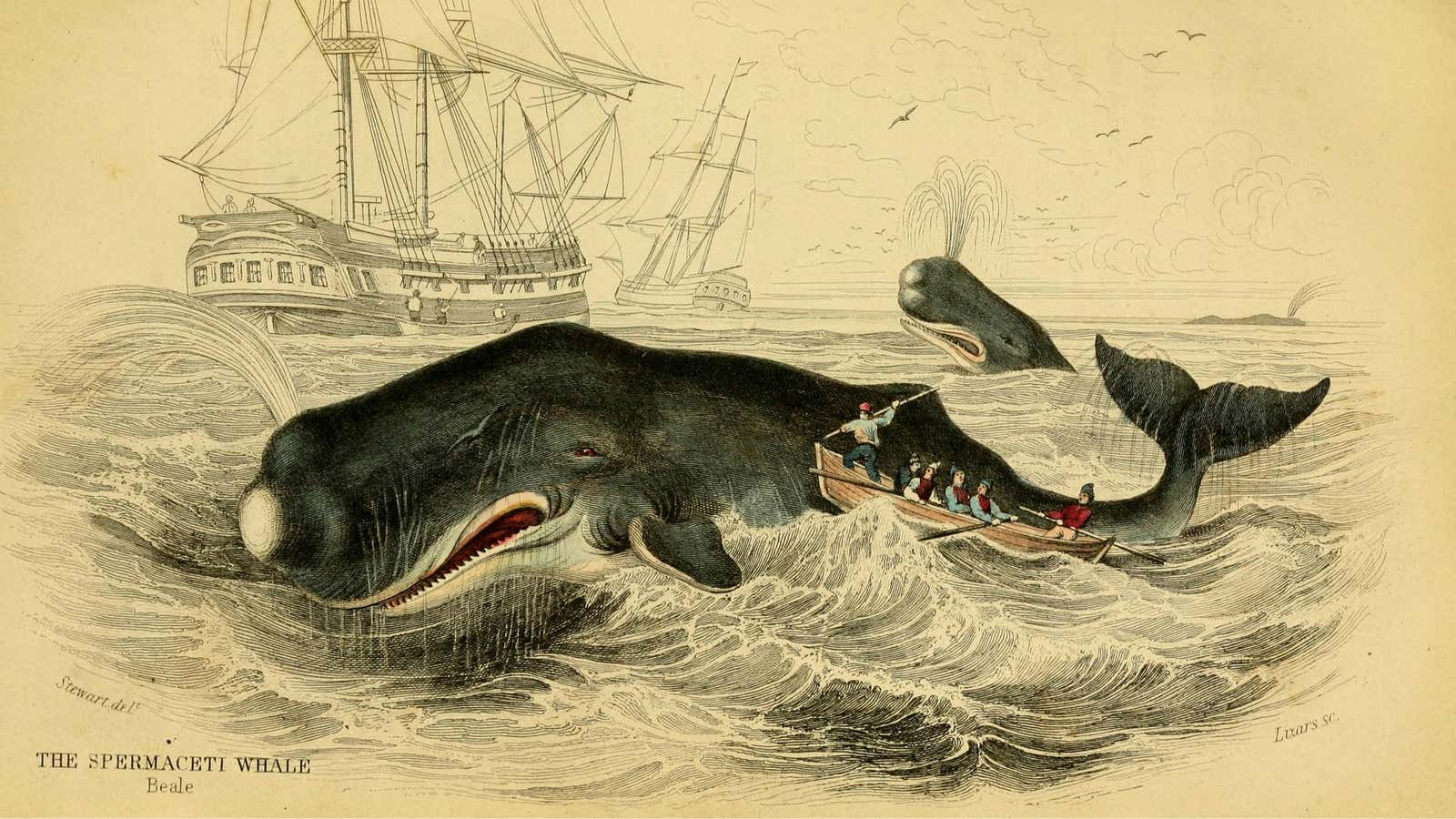

The backdrop to this discussion is, of course, the 19th-century commodity boom in whale products: The oil from their corpses kept machinery lubricated and lamps illuminated, while cartilage was valuable for making corsets (the premium oil known as spermaceti found in the head of the sperm whale was particularly coveted). A successful whaleship would kill somewhere between 25 and 50 whales during one of its multi-year voyages. In 1821, the year the Essex went down, it was one of nearly 90 whaleships from Nantucket, Massachusetts, alone, according to Eric Jay Dolin’s Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America. The total US whaling fleet peaked in 1846 at 735 ships. By 1853, the industry slaughtered more than 8,000 whales a year. That’s adds up to very few whaleship attacks per each whale killed.

Ramming by accident?

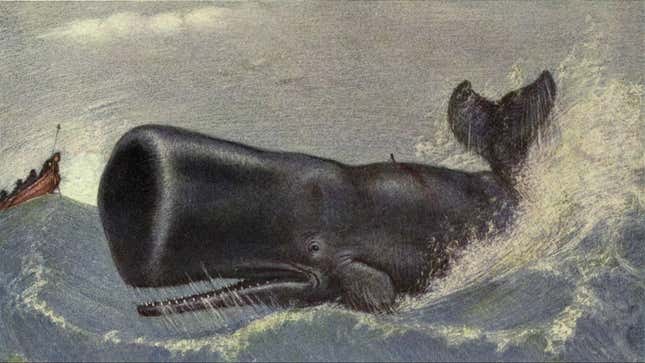

This is consistent with what leading scientists say about sperm-whale aggression—namely, that it’s extremely rare. It’s also not clear that ramming is in the sperm whale attack arsenal, says Hal Whitehead, a biologist at Dalhousie University and perhaps the world’s top expert on sperm whales. In the thousands of hours Whitehead and the other sperm whale experts Quartz spoke with have collectively spent watching the animals, only Whitehead has seen males fighting; the skirmish was brief and he doesn’t recall the two whales ramming each other with their heads (the largest toothed whales in the ocean, males typically fight with their jaws).

Creatures that make their homes in the deep sea, sperm whales have lousy vision and use sound to visualize the objects around them. In a moment of panic, a whale might not notice a whaleship, and therefore might simply bang into it accidentally.

“My guess is that they were primarily mistakes on the whales’ part,” says Whitehead. “The whalers were close to the whales, and the whales were probably trying to avoid the whaleboats [the smaller oar-powered boats from which the crew hunted] that were trying to kill them, and sometimes ran into whaleships, which were lying there quietly.”

It’s also possible the sperm whales were acting in self-defense, says Luke Rendell, a lecturer at the sea mammal research unit of the University of St Andrews, part of the Marine Alliance for Science and Technology for Scotland, and co-author of The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins. For instance, in the sinking of the Ann Alexander, the sperm whale had already been harpooned when it rammed the ship. (Five months later another ship killed the likely perpetrator; the crew found two harpoons and timbers from the ship’s hull embedded in his flesh.)

A case of mistaken identity

As for the attack on the Essex, Rendell says the most plausible explanation has to do with the sounds coming from the ship just before the attack.

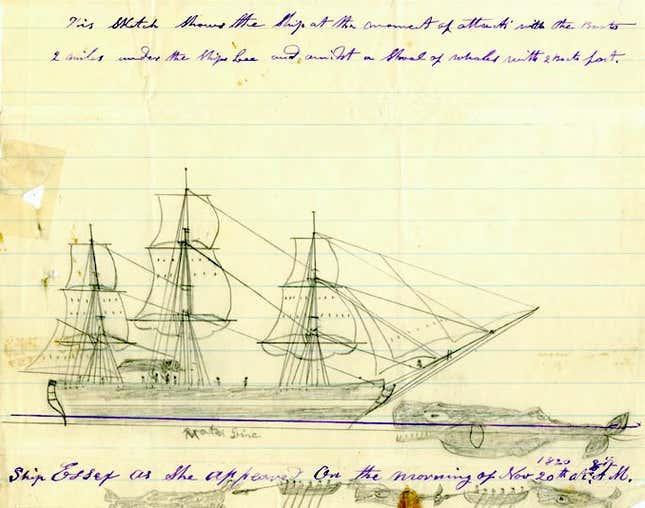

The Essex crew was hunting sperm whales more than 1,000 miles off the coast of Peru when the fateful ramming took place. Upon sighting a shoal of sperm whales, the whalers set upon them in three boats. Two successfully harpooned their quarry; the other boat was forced to retreat from the carnage after a whale bashed a hole in its side with its tail. As the men patched up the the ship’s deck, a huge bull—almost certainly part of the clan of whales being slaughtered in the distance—appeared near the ship and drove its head into the ship’s side; its second blow, a few minutes later, sunk the ship.

The hammering sound made by the men repairing the ship resembles the banging sounds male whales make to communicate with each other, which scientists call the “slow click.”

“We know males compete with each other, we’ve seen it, and since only males make the slow click it’s quite reasonable to suppose that it may function at least partly as an antagonistic signal,” says Rendell. “I have been researching sperm whales since 1993, and the only time I have seen anything remotely approaching aggression to our boat is when we were trialling some sound playback techniques and played these slow clicks to a young male at the surface—it turned around and began swimming towards us, at which point we ceased playback, and it went back to its business.”

Stumpfhaus, the documentary-maker, says something similar may have happened with the Union in 1807. Though it’s supposed that the whaleship sank after accidentally colliding with a sperm whale, the captain’s records report that the ship’s blacksmith was hammering damaged harpoons just before impact. A lack of detailed records makes it hard to know if this sort of banging activity happened in other whale-sinking incidents, but it’s at least possible. In addition to boat and harpoon repair, a ship’s carpenter sometimes had to fix the wooden barrels used to hold the whale oil—another possible source of hammering that might attract male whales, says Stumpfhaus.

In other words, the whale that sank the Essex might have thought it was attacking another male—one that he may have suspected was responsible for spilling his family’s blood into the sea around him.

Scarred for life

Regardless of what the bull males thought when they were ramming the Essex and other ships, the possibility that it might have been an impulse to protect other whales would make also sense. Sperm whale society is matrilineal, with the grandmothers and mothers raising their calves together as families, sharing distinctive cultures and even dialects with the few other families that make up a clan, says Aarhaus University’s Gero. These family- and clan-based societies revolve around cooperation, including the communal defense of calves. Since males are significantly bigger—sometimes two or three times the size of females—their efforts to protect their family would have attracted more attention, says Gero—and made for a better story to swap with other whalers.

We also can’t know how the anguish of having witnessed the slaughter of parents and grandparents might have influenced sperm whale behavior. Because of their similarly close-knit community structures, elephants might offer a useful analogue, notes Gero. Young elephants that experience their family members being killed by poachers suffer a kind of post-traumatic stress disorder that appears to stunt social development and cause, among other things, abnormal aggression among males.

“Given what we know about elephant grieving and trauma,” he says, “it’s interesting to think about what social impact whaling had on this generation of whales.”

With the exception of Nickerson’s drawing, the images used in this piece are courtesy of Biodiversity Heritage Library via Flickr (licensed under CC-BY-2.0, image has been cropped).